They say that beauty is only

skin deep, but can the same be said of hatred?

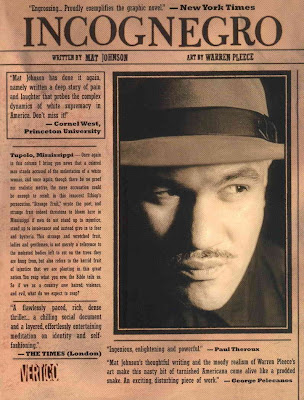

Mat Johnson, primarily an

author of African-American literature, continues his exploration of race in the

hard-hitting graphic novel “Incognegro.”

Released by Vertigo in 2008,

the narrative provides a scathing look at injustice in 20th century America

through the use of historical fiction.

During the late 1800s and

early 1900s, racial violence was commonplace in the United States, particularly

in the South. In an area of the country where the social convention of

segregation was culturally acceptable and later institutionalized by Jim Crow, such

actions constituted efforts to maintain white supremacy and disenfranchise

blacks. Attempts were made specifically to deny them the rights granted by the

Civil War Amendments (13th, 14th and 15th).

Lynching was a form of white

man’s “justice” for violating this social code. For offenses both alleged and

actual, countless individuals suffered the brutality of mob action during this era.

According to the Tuskegee

Institute, nearly 4,800 people were lynched in the U.S. between 1882-1968,

a statistic considered “conservative” by most historians.

Several courageous

African-American journalists who had light skin and were able to “pass” as

white went undercover to bring national awareness to these atrocities, a

dangerous process known as going “incognegro” – hence the title of the work.

Besides the period context,

Johnson provides further realism to the comic by using a real-life individual

as inspiration for his protagonist.

Walter Francis White was a prominent

civil right activist, novelist and spokesperson. He is perhaps most remembered

for his work with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored

People, NAACP, which he joined in 1918. White, who had blond hair and blue eyes

due to his European ancestry, was the organization’s chief investigator of

lynching.

During his 10 years of undercover

work, he chronicled 41 lynchings and eight race riots, providing candid details

of both the events and the perpetrators. His writings were featured in numerous

publications across the country, including the Chicago Daily News, American Mercury and The Nation, among others. His exposés help turn the tide of public

opinion against lynching and resulted in increased federal legislation to

combat the practice.

The story of “Incognegro”

follows the work of Zane Pinchback, a 1930’s reporter who works for the New

York-based newspaper, the New Holland Herald. Pinchback, like the aforementioned

White, investigates lynchings. His experiences are published under an alias in

a widely read syndicated weekly column.

The book begins with Pinchback

planning to retire from his clandestine work, having barely escaped with his

life on his last story after his identity was exposed. However, fate intervenes

in the form of a personal assignment — his brother, Alonzo, has been arrested

and falsely charged with the murder of a white woman in Tupelo, Mississippi.

Thus, embarking on the

infamous “last job,” Pinchback, once again goes “incognegro” to prove his

brother’s innocence. Further complicating the situation is the impromptu

tag-along of Pinchback’s fellow light-skinned friend Carl, who, despite his

inexperience, aspires to take over Pinchback’s job.

With the looming threat of a

lynch mob and the rising suspicions of the townspeople, the story becomes a

frantic race against the clock as Pinchback endeavors to uncover the true

killer, maintain his cover and “get the hell out of Dodge.”

Johnson’s writing style

provides a riveting detective story, complete with many unexpected twists and turns.

The setup of the plot is similar to the classic Sidney Poiter film “In the Heat

of the Night” – a black man trapped in an isolated community, attempting to

solve a crime while also dealing with the escalating tension of the racist

townsfolk.

The overarching theme of

“Incognegro” is one of identity — particularly poignant is how Pinchback and

Carl are treated differently by Southern whites based solely on an outward

element, which we the reader know, is a fabrication.

Pinchback himself recognizes

the superficial nature of the actions:

“That’s one thing that most of us know that most white

folks don’t… [R]ace doesn’t really exist. Culture? Ethnicity? Sure. Class, too.

But race is just a bunch of rules meant to keep us on the bottom. Race is a

strategy. The rest is just people acting.”

The opening scenes of the

book hold nothing back – the first three pages show a lynching in progress in

graphic detail, complete with a voiceover description of the process.

This harsh, no-holds-barred presentation, which continues with copious uses of the "n-word" and other derogatory terms, provides the necessary shock value to forcefully immerse the reader in the

world.

These arresting images are

different from other instances of violence in comic books. Unlike other intense

visuals in comic books by writers such as Garth Ennis and Mark Millar, the

shock of these scenes cuts deeper, due to the knowledge that events like these

actually happened in a previous era of our nation’s history.

The appropriately

black-and-white art of Warren Pleece perfectly exemplifies the time period — he

has a very subdued grounded, simplistic style of drawing, focusing on tight

shots of his characters to emphasize their expressions and dialogue. His inking

utilizes shadows, giving the story a noir-like feel. Large images are used

sparingly, specifically only when to highlight a moment.

“Incognegro” is a fantastic

graphic novel that brings new life to an important time in our history via an engaging medium. It is a must-read for those who appreciate the

past and the advancements made in both African-American and the general

culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment